Tags:

Summary:

Acting before a shock to prevent its impact on people, is known as anticipatory action in the humanitarian sector. A predictive model or forecast used to trigger pre-agreed action plans and pre-arranged finance makes anticipatory action possible. But what happens when there isn’t sufficient forecast data available, or in a complex operating environment more time is needed to prepare? Is it still possible for the humanitarian community and the UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) to release funds ahead of an impending crisis?

These were some of the questions the Centre’s Data Science team and OCHA colleagues were confronted with when planning anticipatory action ahead of floods in South Sudan in 2022.

Challenge:

Communities across South Sudan had already been suffering from three years of unprecedented flooding. More than two-thirds of the population (almost 9 million people) needed humanitarian assistance. Ongoing conflict and instability in the country combined with the flooding resulted in people being forced to leave their homes time and time again.

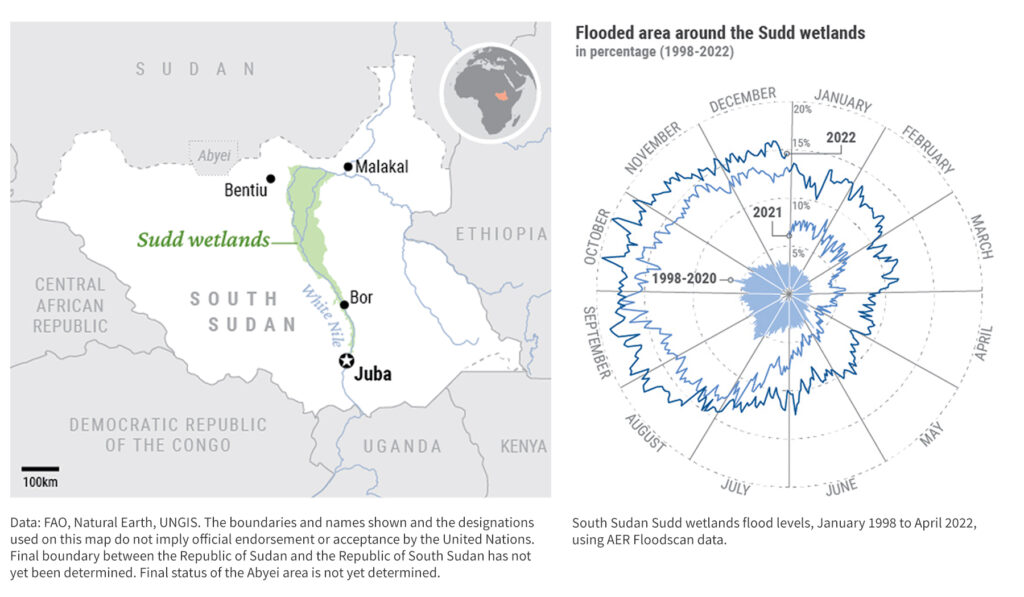

In March 2022, the Centre explored available forecasts in South Sudan to establish an Anticipatory Action Framework to get ahead of future floods. However, the complex nature of the Sudd wetland’s ecosystem meant there was no reliable forecast to trigger time-bound actions for a framework. But the Centre’s analysis did confirm there was enough information to indicate a significant flood was looming.

Typically, during the dry season flood waters retreat into the Nile and other river basins, drying out the land and preparing for a new rainy season. However, the flood waters from 2021 had not receded and remained above the highest levels observed in over 20 years. Any new rains expected for 2022’s rainy season would turn an already dire situation disastrous.

In Unity State, the flooding was expected to put more than 320,000 people – over a third of whom were already out of their homes – at risk of further displacement, loss of livelihoods, disease outbreaks, food insecurity and psychological distress.

In Unity State, the flooding was expected to put more than 320,000 people – over a third of whom were already out of their homes – at risk of further displacement, loss of livelihoods, disease outbreaks, food insecurity and psychological distress.

More than 125,000 people living in a camp for internally displaced persons (IDP) and in informal camps in Bentiu town were particularly vulnerable and at risk. Bentiu surrounded by floodwater was cut off from dry land and roads, protected by kilometres of hurriedly constructed dykes. With very limited opportunity for livelihoods and reduced access to aid, people were extremely food insecure – at times resorting to eating water lilies. Even a relatively small increase in the water level or a dyke breach would have catastrophic impacts.

Not only was the Bentiu IDP camp at risk of being submerged, so was the site of Unity State’s humanitarian operations.

The humanitarian community had merely a few weeks, perhaps months, to prepare before the rainy season began.

Outcome:

OCHA saw an opportunity. Pilot a lighter and nimbler approach to anticipatory action where CERF funds could be provided earlier based on a high likelihood of the country experiencing an additional shock that would compound existing humanitarian needs.

CERF pulled the response forward by allocating US$15 million, complemented by an additional $4 million from the South Sudan Humanitarian Fund (SSHF) in May 2022, months sooner than had been the case in response to the 2020 and 2021 floods.

Alongside the funding, Sara Beysolow Nyanti, Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator in South Sudan, put in place decision-making as close to the people of Bentiu as possible. A high-level special task force was established with senior representatives in Bentiu to consult with communities on their priorities and to oversee operations.

Ahead of the floods, partners used the funds to construct and reinforce over 55 kilometers of dykes to protect vital access roads, homes and the airstrip. These dykes would prove to be critical, preventing 100,000 people from having to be evacuated and further displaced, even as IDP camps sank below water-level at the peak of the flooding. A previously flooded road between Bentiu and Mayom junction was reopened, providing a key supply route for essential goods that increased the volume of supplies and was estimated to be four times cheaper than having to fly in supplies. Protection of the airstrip allowed humanitarian operations to continue throughout the rainy season – a lifeline for the people of Bentiu.

Early investments in latrines, water treatment sites, and cholera vaccine campaigns helped to avert a public health emergency.

Cash transfers to over 1,000 female-headed households, the majority of whom had at least one family member who was older or with a mobility impairment, enabled them to reinforce their shelters.

“On the whole the money that came in helped quite a bit with mitigation for flooding… Other locations in the camp set up dyke committees and trained people immediately. Materials were bought, and tools, and people were able to use the tools to reduce flooding in their sites,” says a UNHCR informant.

Conclusion:

In protracted crises and conflict settings there is not always enough time, data or access to develop an Anticipatory Action Framework. South Sudan shows this should not stop humanitarians from acting ahead of a shock. Anticipatory action principles can be taken and adapted to context-appropriate programmes.

“The takeaway is clear: anticipatory action works for climate-related shocks in South Sudan, but also elsewhere, including in Mozambique as I saw during my recent visit,” observed Joyce Msuya, Assistant Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Deputy Emergency Relief Coordinator. “Government-OCHA collaboration on early warning, combined with proactive community engagement, saved lives and resources. This cost-effective, flexible approach helps minimize suffering.”

OCHA continues to facilitate coordinated anticipatory action and has expanded its portfolio of pre-arranged funding to more than $100 million in 15 countries for storms, floods, droughts and cholera. CERF is also inviting applications for funding anticipatory action to get ahead of predictable humanitarian impacts of El-Niño-driven climate emergencies.

The Centre is also expanding its work on risk analysis to support early action in other contexts, including through its pilot and partnership with Google’s Flood Forecasting Initiative to provide automatic alerts to decision makers when flood levels are forecasted or observed to rise across the Niger and Benue river systems.

Learn more about the anticipatory approach to the 2022 South Sudan floods: Innovating Anticipatory Action: Lessons from the 2022 South Sudan Floods.

Find more information on our Anticipatory Action and Data Science pages.