Share

The Centre talked to Derval Usher, the Head of Office for Pulse Lab Jakarta, a joint initiative of the United Nations and the Government of Indonesia. Pulse Lab Jakarta is part of UN Global Pulse, a flagship initiative of the United Nations Secretary-General on big data and artificial intelligence. Its vision is a future in which big data is harnessed safely and responsibly as a public good. We discussed how the Global Pulse lab network works with the private sector, the importance of human-centered design, and what success looks like.

The interview was conducted by Elizabeth Wood, the Centre’s Communications Manager. It has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Tell us how Pulse Lab Jakarta got started.

Each UN Secretary-General comes on board with their own special interests. One of Ban Ki-moon’s was on big data and how to use it for development and humanitarian purposes. When Global Pulse in New York was established as one of his special initiatives, the whole idea was to harness non traditional data sources to inform the MDGs, the precursors of the SDGs. After that, two more labs were set up: one in Jakarta, Indonesia which I run, and the other in Kampala, Uganda.

We’re an experimental lab, so there should be experimental value to the work that we do. We’re not interested in doing anything that’s already been done. We look at digital data sources to see how we can analyse those for public good. We do a lot of mentoring and facilitation using new methods. We’re coming up with new research and new collaborations. The development, humanitarian, peace and security sectors have tended to be quite siloed until recently and so we are asking how can we collaborate across sectors? How can we bring in the private sector to collaborate at scale? With a focus on the SDGs, how can we harness the digital revolution for public good?

“Data science is not something that can be done very easily, or quickly. I think that’s a misconception about data science in general. Context matters. ”

-Derval Usher, Head of Office, Pulse Lab Jakarta

What are some of the ways the team is working with the private sector?

UN Global Pulse is the custodian of an agreement with Twitter, which enables organizations within the UN to get access to and analyse Twitter data to help close information gaps. We’re also discussing with other companies — social media and mobile operators — on how to bring their anonymized disaster related data into our data analytics platforms. In the Asia Pacific region, social media usage for example is highly ubiquitous. Therefore when a disaster happens, such as the earthquake and subsequent tsunami in Indonesia in Palu, South Sulawesi last September, many people will update their social media and document their movements online. Not everybody of course, but a lot of people will use their mobile phones as well. If we can glean information that’s coming through Facebook safety check-ins, or if we can use mobility information to understand where people are moving to and from, we feel that’s an important advancement when it comes to understanding humanitarian needs in a more efficient, quicker manner.

Are there any risks to working with dynamic datasets, such as those collected from social media?

It’s really important to understand that analysing big data is all about uncovering patterns so we do not look into individual behavior. We only analyse anonymised datasets. Data privacy is particularly important for us and discovering whether we can use big data responsibly and ethically for development and humanitarian action. The interesting thing is if you actually combine location with keywords such as ‘no water,’ ‘massive floods,’ ‘death,’ or whatever the needs are, a pattern starts to emerge. That’s what we are interested in.

There’s also a lot of noise on social media that you have to look out for, so it’s all very much an iterative process. One example, which we did in our early days, was trying to monitor food prices on social media. A major commodity here is chicken. In Bahasa Indonesia, the word for chicken is ‘ayam,’ but when you come across ‘ayam’ on social media, it’s also used for a variety of different contexts. What our data science team is trained to do is extract the insights from the noise and train the algorithm on keywords before and after ‘chicken’ to make sure it is food-related. Data science is not something that can be done very easily, or quickly. I think that’s a misconception about data science in general. Context matters.

How does Pulse Lab Jakarta work with local government?

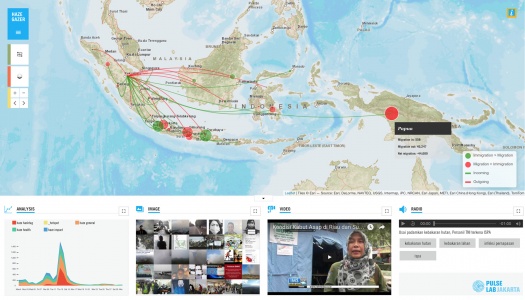

Pulse Lab Jakarta was set up as a joint initiative of the Government of Indonesia and the United Nations and so all our projects are focused on national priorities. Together, we created a tool called Haze Gazer, which monitors haze and forest fires across Indonesia. These are huge problems and lead to a lot of air pollution. We worked to combine big data with citizen-generated data. When you start combining what people are saying on the ground with the locations of the forest fires, it becomes extremely useful information.

Rather than just say, ‘there’s a hundred fires going on in Indonesia at one time,’ what you are able to say is, ‘in this particular location, there are X number of people talking about how their kids haven’t gone to school for two weeks,’ or ‘this local hospital ran out of respiratory-related medicines three weeks ago’. That information gets fed back to the central government to help with their emergency response programs. The Haze Gazer system is actually installed in the Executive Office of the President of Indonesia. And based on what we’ve learned from this tool, we’ve been able to create other tailored systems to aid disaster prevention, monitoring and response for Indonesia and other countries across the Asia Pacific region.

What are some of the data challenges you face working in this region?

Indonesia’s a big country, often without common maps and datasets. If you ask the Ministry of Agriculture how much rice is in the country, they have a different number compared to the Ministry of Trade, who have a different number compared to the Rice Bureau, and so it all gets really confusing. We worked with the Government to come up with human-centered design principles for data governance. We created a toolkit for government officials on how to model a data governance framework at the local level. That was a really interesting project and the Government was thrilled with it. It was very important to them, and we had the skills that were needed so we were happy to do it.

How does human-centered design guide your team’s approach to innovation?

We actually have a human-centered design department. What we found is that you can get carried away with new methodologies and producing really snazzy platforms and dashboards that look amazing, but they are not actually maintained and used. We always want to have that link to user needs and evidence-based policy making. Our added value is getting people to use evidence in a different way. With human-centered design, we focus on understanding the experiences, needs, and pain points of the end users.

How does your team use HDX?

We share a team member! Our humanitarian data analyst is recruited by both HDX and Pulse Lab Jakarta and he works specifically on humanitarian data projects in our region. When we design new humanitarian projects or organize workshops, he talks about what HDX does and what Pulse Lab Jakarta does. It’s kind of a dual purpose – if he can convince the government that they should be sending datasets to HDX then obviously that’s good for us, too.

In fact we collaborated with HDX recently for the launch of our latest research tool called MIND, which stands for managing information for natural disasters. MIND is an open source tool that integrates several datasets to inform information management following natural disasters. Some of the datasets that are featured in the MIND platform come via HDX. At the launch event, Ms. Ursula Mueller, Assistant Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Deputy Emergency Relief Coordinator in the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA) discussed the benefits of having open data sources that can be accessed easily and quickly to aid disaster response efforts.

We’re so happy that HDX exists as a means to open datasets and make them usable for everybody else. What we would love to see is a combination of data that’s coming out of HDX together with data that’s quite active and fast-paced, like the social media data I mentioned for example which is so important for the dynamic nature of the Asia Pacific region.

How does Pulse Lab Jakarta measure success?

We have platforms that are used within the government of Indonesia’s system. I would call that a success, to have adoption at scale. We track what we call our stories of change. With all of our projects we ask, ‘what was the change process that happened from when we came up with the prototype’ and then, we track that back.

I’m so happy to be working with the people in my team. We have a great deal of flexibility and freedom to innovate and be creative within the public sector. I love my team of young, passionate, smart people who really want to create new and exciting solutions for public good. Still, the grand plan is that in the next five years, we put ourselves out of business, so to speak, because other parts of the UN system and the Government of Indonesia would be doing data analytics by themselves and so there’s no need for us anymore. For me, that would be a real measure of success.

To learn more about Pulse Lab Jakarta, go here. Follow them on Twitter @PulseLabJakarta