Share

[Aussi disponible en français]

In July and August 2015, the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) team deployed a lightweight, standards-based system for tracking the training of health workers in Guinea. Front-line health workers were at high risk during the West African Ebola epidemic: over 700 of them became infected with the Ebola virus. Ensuring that health workers were trained to protect themselves from infection became a critical part of the response, and involved more than a thousand formal and informal health facilities across Guinea.

In order to improve coordination of USAID/OFDA-funded Infection Prevention and Control interventions, the USAID Guinea Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) asked the HDX team to set up a system for tracking health worker training in infection prevention and control. This system would allow the DART and the IPC cluster to identify gaps in training and prevent duplications of efforts on the part of IPC partners. The data tracking system was deployed over a two week period and consisted mostly of existing components, like HDX and Dropbox, tied together by the Humanitarian Exchange Language (HXL), an open data interoperability standard.

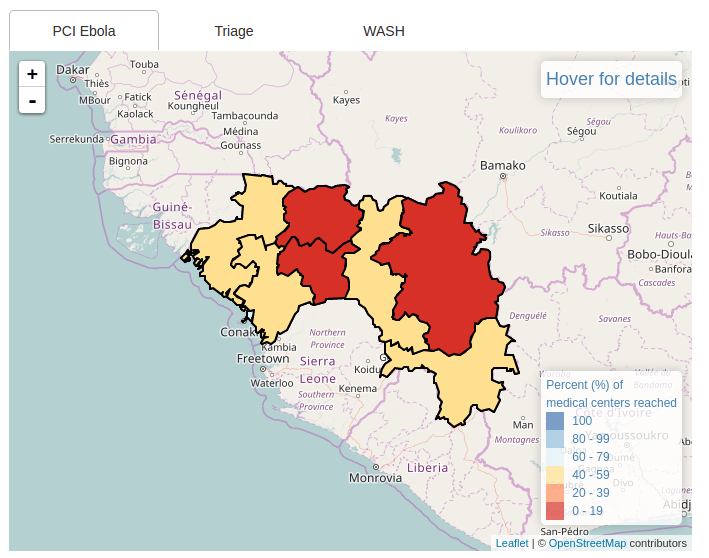

Dashboard: Training coverage by region

The initiative was inexpensive and technically effective, and received positive feedback from partners. However, it took longer than expected for the partners to begin sharing data and provide updates on trainings, and the sharp decline in Ebola infection rates after we started meant that the need for the system subsided before we could test it over an extended period of time.

Deploying the system

As in most data-sharing exercises, we began with a spreadsheet template approved by the Ebola National Coordination Cell and reporting organisations. Our template was a little different, because it also included HXL hashtags so that we could automate tasks like data merging, validation, cleaning, and reporting.

For each reporting organisation, we created and shared a separate Dropbox folder. Each organisation had access only to its own folder, so there was no risk of accidentally moving, overwriting, or deleting another organisation’s files (a common problem when using Dropbox for multi-organisation sharing).

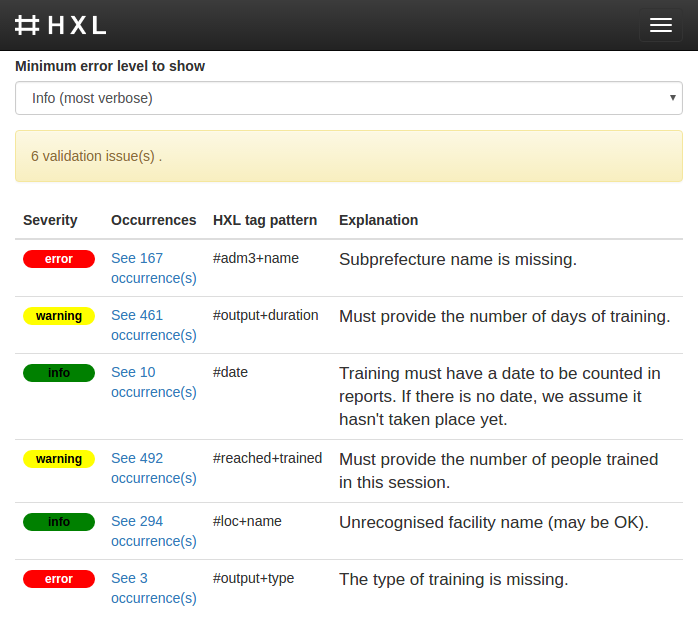

Live feedback for reporting organisations

The open-source HXL Proxy allowed us to set up an interactive validation dashboard for each organisation, like the one pictured. Whenever members of an organisation saved a new version of its reporting spreadsheet to its Dropbox folder, they could get near-instant feedback in a browser window driven by a customised HXL Schema.

The batch-processing involved five steps:

- Validate each partner spreadsheet to make sure that it contains properly-formed HXL data.

- Merge the individual partner spreadsheets into a single common dataset.

- Fix common misspellings and similar minor data errors using the table of corrections.

- Expand the merged dataset, adding P-codes (geographical codes) from the master data.

- Make the updated data available on the HDX IPC Guinea dataset page, including custom dashboards that updated instantly for data changes (see dashboard image above).

The entire processing run took under 10 seconds (compared to hours or days for typical manual spreadsheet work), and was easy to repeat whenever a partner organisation uploaded a new dataset to its Dropbox folder.

Results and lessons learned

Building a data system from simple, available components worked well. For a small fraction of the cost and time of a sophisticated, custom-built application, we had a multi-user, end-to-end data-management system, from initial data collection to live operational dashboards. The HXL hashtags allowed automation and data interoperability even when the source data wasn’t perfectly clean. HDX was a lightweight but effective platform for sharing the data, both with the Ebola National Coordination Cell partner organisations and with the wider humanitarian community. One unanticipated drawback of using free cloud services is the inability to collect analytics to measure engagement—we have no easy way to determine, for example, how many times people have downloaded the core IPC dataset (hosted on Dropbox) or viewed the dashboards (hosted on GitHub).

While the technology was straight-forward, we did underestimate some of the other challenges. Because of different needs and abilities within the group of reporting organisations, it took us longer than expected to get consensus on a simple reporting template. Face-to-face meetings—while essential—were time-consuming and unpredictable in Conakry during the flooding of the rainy season (and many might not have happened without the tireless support of the USAID DART). We realised that even simple spreadsheet skills were not widespread among organisations whose main skills were in the health sector, and our local OCHA staff had to invest considerable time in training and support during the weeks after the initial deployment. Finally, data arrived slowly, even with the constant encouragement from USAID (the primary donor for most participating organisations), and strong positive feedback from the participating organisations. By the end of October 2015, 8 of the 14 organisations who initially expressed interested had shared data about 1,196 training activities.

In the end, the pilot was overtaken by a positive event: the Ebola infection rate declined rapidly in the months immediately after the pilot launch. As a result, infection prevention and control lost its urgency, donors and NGOs shifted attention to other health crises, and the flow of data dried up before the system could run for an extended period of time.

Next steps

With support from the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, we have established up a data lab in Dakar, Senegal to support our partners on data efforts across West Africa. The lab will build on the lessons we learned during this project.

Thanks

A large and dedicated team contributed to this project. Thanks to the Guinea IPC partner organisations, to Dr. Fodé Badara Conté from the Guinea Health Ministry, to the USAID Guinea DART (especially Dr. Linda Mobula, Kate Farnsworth, Marsha Michel, Allen Carney Julie Leonard and Issa Bitang), to the country teams from the Center for Disease Control and the World Health Organisation, to the now-disbanded OCHA Guinea Office (especially head of office Noel Tsekouras and IM specialist Clément Karege), to Eric King (then at USAID’s Global Development Lab) and to the HDX team itself, especially Simon Johnson, who created the dashboards.

If your organisation is interested in collaborating with us on humanitarian health data in the region, please send a message to hdx@un.org.

Update: USAID published a wide-ranging collection of case studies covering the Ebola crisis at this link.

[…] [This post is also available in English.] […]